“Someone’s Assassin:” Subverting Femme Fatale Tropes and Why Elektra Remains One of Marvel’s Greatest Antiheroes

Elektra is one of Marvel’s most fascinating characters and has been all too often mistakenly shrugged off as one of its most one-note. She is, to say the least, not all that in touch with her emotions and this often leads people to incorrectly assume her character is flat or uninteresting. That couldn’t be further from the truth, of course, but the perception remains unswayed even after her appearances in both film and television, some of which treated the character better than others. In fact, treatment of the character in general is its own conversation, as she has been subject to some of the most notable fridging in comic book history.

For those unfamiliar with the term, fridging was coined by comic book writer Gail Simone to note when a female comic character (usually the male hero’s girlfriend) is killed off in order to further the hero’s motivation or development of his character. With Elektra, this goes all the way back to her introduction in the pages of Daredevil. Making her debut in Daredevil #168 back in 1981, Elektra made an impact in what is now regarded to be one of the best runs in Marvel’s entire history if not comics in general. This was the series that cemented Frank Miller as a superstar writer and artist.

Elektra was originally intended to be a one-off assassin for Daredevil to fight, visually inspired by bodybuilder Lisa Lyon, but both Marvel and Miller were enticed by the character and kept bringing her back, expanding her origin as they did. Elektra Natchios was revealed to be the college girlfriend of Matt Murdock, AKA Daredevil. After being trained under Matt’s mentor, Stick, Elektra ultimately succumbed to her inner darkness and sided with the mystical ninja organization known as The Hand. She moved back to New York under the Kingpin’s employ as a free agent, where she crossed paths with Matt again, who had by this time become Daredevil.

There’s a lot to unpack there, not only in the character’s history but how she was introduced and used in those early appearances. A beautiful woman from the hero’s past who is destined to only bring destruction down on him, that’s a very obvious femme fatale trope, hell, that’s pretty much the definition of femme fatale. But this is inverted, even in those early issues, by the fact that it is by and large accidental. Elektra does not know that Daredevil, the man she’s been hired to kill, is also Matt Murdock, her former lover. This is not the noir trope of a woman coming into a man’s life to wreak havoc and dismantle it, it’s almost more of a twisted comedy of errors.

Elektra certainly embodies the trope in that she does often use her sexuality to get what she wants, even if that is not really the case with Matt. Even this, though, plays out a little differently than the typical femme fatale. Elektra’s attractiveness is something she uses to her advantage, but only as much as any other tool. She has an almost dispassionate relationship with her own body, it’s really nothing more than a means to an end. She can easily feign desire if it means getting closer to a target, but the only real sexual chemistry she ever seems to have is with Matt. There, it comes from a place of honesty, it’s a raw and natural energy that isn’t manufactured in the way it is with everyone else.

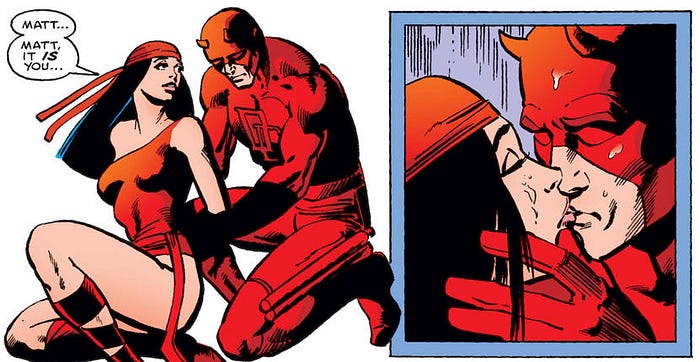

On that note, let’s break down the Daredevil/Elektra relationship, because while its approach to sexuality as an almost spiritual connection — or even in some ways a physical form of expression between two people who are not terrific with words — there are also plenty of negatives. First and foremost, there’s the fact that after a (very brief) college relationship, Elektra’s next appearance in Matt’s life is in attempt to kill him. It is destructive in extremely obvious ways, but before leaping into that, one needs to look at the initial relationship, because it was very brief. Both Matt and Elektra, now adults with very different professional lives, have spent years idolizing what was in essence a college hookup. The relationship was never what they probably thought it was because it never had time to be. But it’s an easy thing to obsess over and even to fetishize, this notion of the one time they found someone who truly understood them and more than anything represented the only time in their respective lives where they felt like they actually understood themselves.

That’s not surprising, in some ways, as that’s literally what college is all about. It’s about being in a totally new environment for the first time in your life and finding the people who help to teach you about yourself. For Matt, it was a time of unwavering idealism, to both law school and his training to become the vigilante he is someday going to be. He’s not as jaded about the law when he meets Elektra, and his doubts about whether one person can make a difference are far from fully formed. For Elektra, on the other hand, it’s about maintaining a personal identity for the first time in her life. It’s about not being tied to her family’s legacy or name, nor any of the false faces she’d have to wear for most of the rest of her life afterward, being whoever she was needed to be for the first time. That brief stint in higher learning was probably the only time in Elektra’s life she was both allowed and encouraged to be herself, so it only makes sense that she would idolize it and in doing so, idolize Matt.

Daredevil and Elektra are probably the closest thing Marvel has to the dynamic presented by Batman and Catwoman. In fact, there are a lot of similarities between the two sets of characters, and they are frequently compared. There are huge differences though, with the biggest of them being that Batman and Catwoman ultimately bring out the best in each other. For all of the reasonable doubts they have in that they are defined by very different ideologies, they do tend to elevate one another. Batman sees a drive to help people that Catwoman can often tries to ignore, while she sees a humanity in him that he tends to insist isn’t there. Matt and Elektra, on the other hand, bring out the absolute worst in each other.

Their relationship is incredibly destructive and worse, both of them are entirely aware of it. The second season of Marvel’s Daredevil on Netflix, for all the structural flaws people love to point out, actually nailed this aspect. On their own, they are already self-destructive people and together they just amplify those qualities. There’s something intoxicating about avoiding their own lives — or even watching their lives crumble — while they’re with one another. It is, for both of them, a form of self-punishment, but one they can’t help but glorify all the same.

Of course, the relationship as rivals, lovers, enemies or any combination thereof did not last long in Miller’s original comic run because Elektra was infamously killed off in issue #181, hence where the “fridging” debate comes in. The issue works as a piece of deft, dramatic storytelling. It’s exactly as shocking and heartbreaking as it was meant to be, with Elektra being fatally wounded by Bullseye, crawling to Daredevil and dying in her former lover’s arms. It’s maybe one of the most painful single issues of comics of the era, and it would have been a huge disservice to the character had it been remotely permanent, as she had still only just been introduced at the time.

It wasn’t permanent, however, and Elektra has been killed over and over again since that time in numbers that only rival those of the X-Men’s Jean Grey. Like Jean, Elektra’s died more times than one could count, even twice on screen. Having said that, these stories after her initial death are not to be dismissed as they are where the bulk of her great character work comes from. Initially, Frank Miller was pissed that Elektra kept making appearances after his initial solo book for the character, as he had assumed he would be the only one allowed to write her on the grounds that he owned the character. That obviously did not turn out to be the case and, with no disrespect to Miller, thank God for that. Miller told some interesting stories centered on Elektra, but this is a character that screams for other voices and other portrayals, so I’m beyond glad she got to have them.

As these solo books went on, Elektra’s personality began to shift ever so slightly. It was really unavoidable. For all she may have been a deadly assassin, in those early Daredevil issues, she could only really be identified through the lens of “Daredevil’s old girlfriend” or “Kingpin’s assassin.” She never got the chance to carve a center role for herself until she started to get her own books. And since that time, she’s gone through some huge changes. And these changes weren’t made to her personality, necessarily. There’s a stoicism to her that has been there from the beginning. But the way that personality has been moved to the forefront over time has changed.

In more recent eras of the comics, Elektra has been characterized in many different ways: as the leader of the Hand, as an assassin for hire, as a vigilante, and all of these things are a part of her character, but taking them on their own and defining her at different times, they are all also traditionally masculine, even macho, qualities. When Elektra takes over the Hand, she’s basically a mob boss, she’s not altogether different from the Kingpin and even if she thinks there’s a justification for why she’s doing it, that does tend to be a thing that all mob bosses think. She might be running a ninja clan, but this is Elektra as a gangster, make no mistake. And she does it much more interestingly than guys like Silvermane and Hammerhead, because there’s so much that can be done with this stale position in the Marvel Universe when it’s given a female perspective. That’s not to undercut characters like Madame Hydra or even Emma Frost in her villainous days, I understand that many female characters have spearheaded evil organizations, but they don’t always reach quite the Goodfellas level of moral gray area that Elektra got to see when spearheading The Hand.

And I do understand that the version of Elektra who led the Hand for the longest period did turn out to be a shapeshifting Skrull. That does need to be taken into account. But that Elektra didn’t know she was a Skrull, nor did the people working on her books at the time. If anything, I’d count it among one of the many times Elektra was killed off for no good reason, Skrulls be damned.

By and large, though, Elektra’s post-Miller appearances — though they often range middling-to-great — have depicted her as an almost macho antihero type, despite her often scant ensemble. If anything, her appearance juxtaposes well with her aloof, dispassionate demeanor. That’s not to say her costume isn’t one of the most impractical in comics, it is. There is no way that everything should stay in place, and many have reimagined her clothing in recent years to make more sense. At the same time, function and practicality are everything to Elektra and she’s probably someone who would do her job butt-naked if she could, if only to not worry about anything snagging and slowing her down. There’s also an element of the costume’s impracticality that suggests how much she doesn’t care about how people see her and how much it’s not on her if they do. She’s an assassin, if something does pop out in battle, she knows damn well that it doesn’t matter because she’s confident it’s the last thing you’re ever going to see.

The clothing does not matter nearly as much as characterization, though. In her solo (and most guest appearances) Elektra has been a kind of rogue agent, a quiet, intense and self-serious anti-hero that often falls somewhere between Wolverine and The Punisher. In her 1996 solo series she even tried her hand at playing hero, spouting off the same embarrassing tough guy one-liners that Wolverine was apt to spew during that era. In fact, Elektra has made more than her share of appearances in both of those characters’ solo titles over time. But there’s also DNA in there that dates back to everything from Dirty Harry to Snake Plissken. Naturally, women have often embodied typically masculine action hero roles, with Ellen Ripley and Sarah Connor being the most obvious examples. Elektra is an interesting middle ground though in that there’s not necessarily a sacrificing of typically feminine qualities, but rather a juxtaposition of female perspective and worldview — Elektra, for example, has a deep understanding of truly global patriarchy because she’s seen it from every single angle — with a rough, curt and aggressive demeanor that’s typically embodied in guys like Logan.

Part of what makes it so exciting to even see Elektra as a free agent at all, be it in her own titles or appearing in others, is the fact that her very being (early on) was defined by powerful men. Her father taught her how to behave like a lady and, naturally, only taught her ideals for a male wishlist of female behavior. He could only teach her what men want women to behave like without another female voice present to really tell her anything to the contrary. Kingpin was, of course, another very powerful man in her life, but by this point it became abundantly clear that Elektra had become an expert in knowing exactly what men wanted to hear and how to spin their arrogance and idiocy to gain the upper hand, usually without them even realizing she’d done it.

And therein lies another point as well: while Elektra has much of the same personality as a tough rogue like Snake Plissken, she never quite has the same level of reverence. Her skills as an assassin are known the world over, in the right circles people might speak of her in a low whisper, yet somehow at the same time she is constantly underestimated. That’s one of the biggest things that tends to separate Elektra from so many similar male characters: she doesn’t need everyone in the world to know who she is to feel like she’s good at her job.

Elektra is someone who began life as an idealized, classical feminine villain trope and wound up embodying many classical male antihero traditions as well, embracing and subverting them at the same time. She is, at the end of the day, the best there is at what she does, but she doesn’t need to make that a catchphrase in order to know that it’s true.